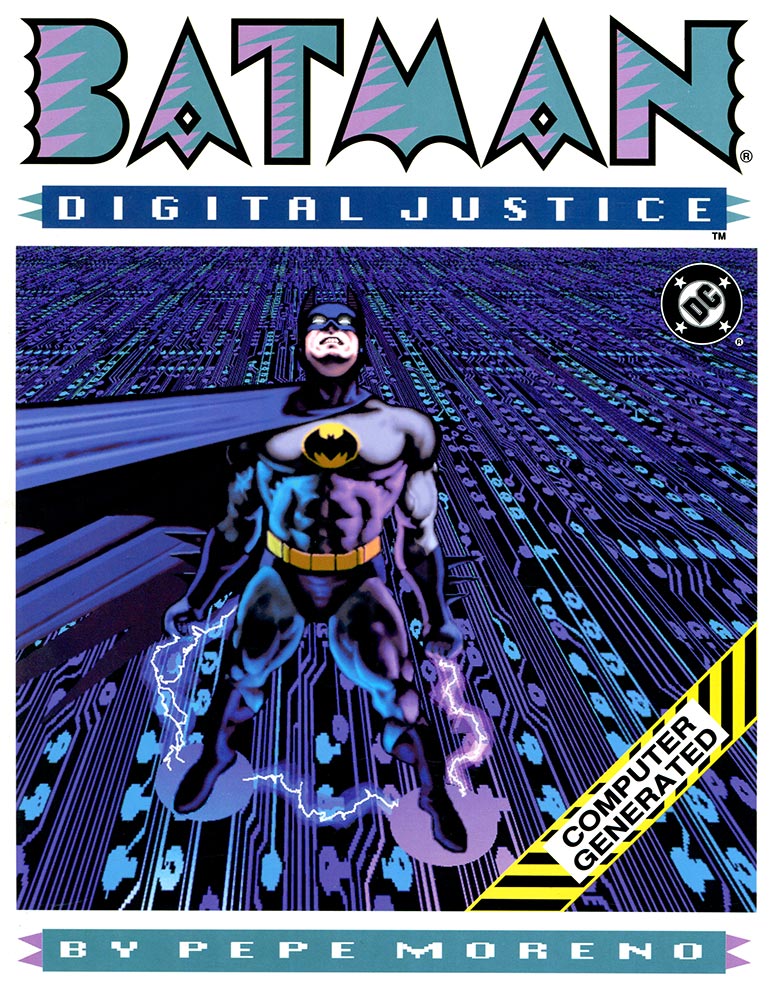

while 1988 saw prometheus steal color, 1990 gave him painting.less than five years after 1985's "shatter", the first entirely computer-generated (cg) comic series and less than two years after 1988's "crash", the first full-length cg graphic novel — featuring marvel comics' invincible iron man — artist pepe moreno, still a relative newcomer who'd assisted in illustrating "crash", brought the ever-accelerating desktop computing revolution to one of the biggest properties in mass-market comics:

between 1937, when the first all-original comic book come out, and the release of the first computer-generated comic in 1984, the tools used in the creation of comic art remained fairly stagnant. that all changed with the introduction of the first affordable graphics-oriented computer. all of a sudden, we had a machine that could do anything. most miraculously, that bottomless box of microchips and cathode rays has allowed our medium to grow — from the standpoint of technology — more in the ensuing five years than it did in the preceding forty-seven.

— mike gold, editor, dc comics

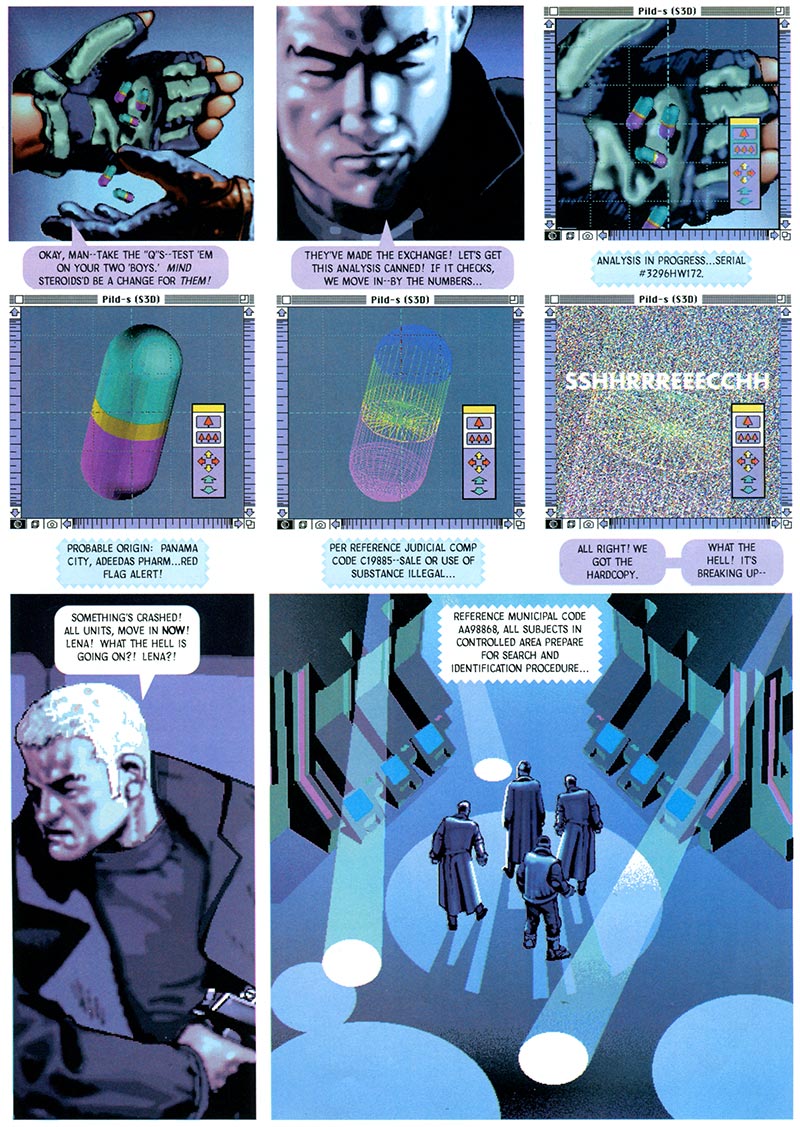

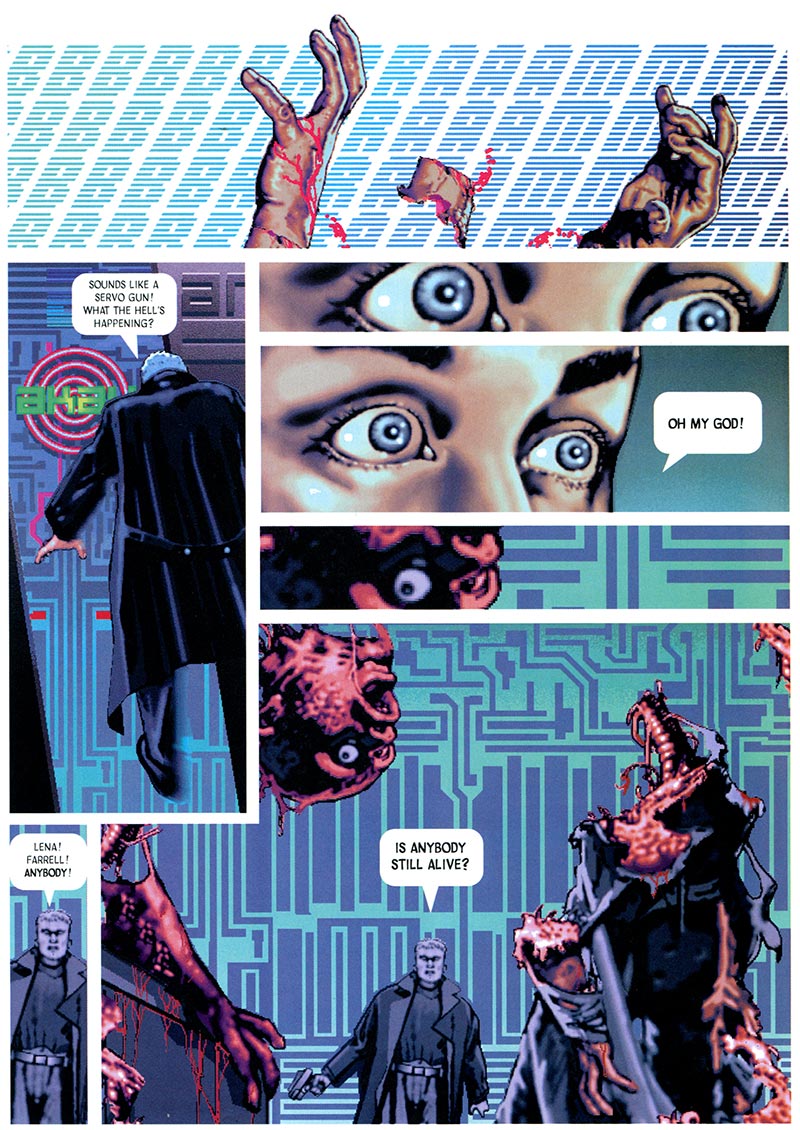

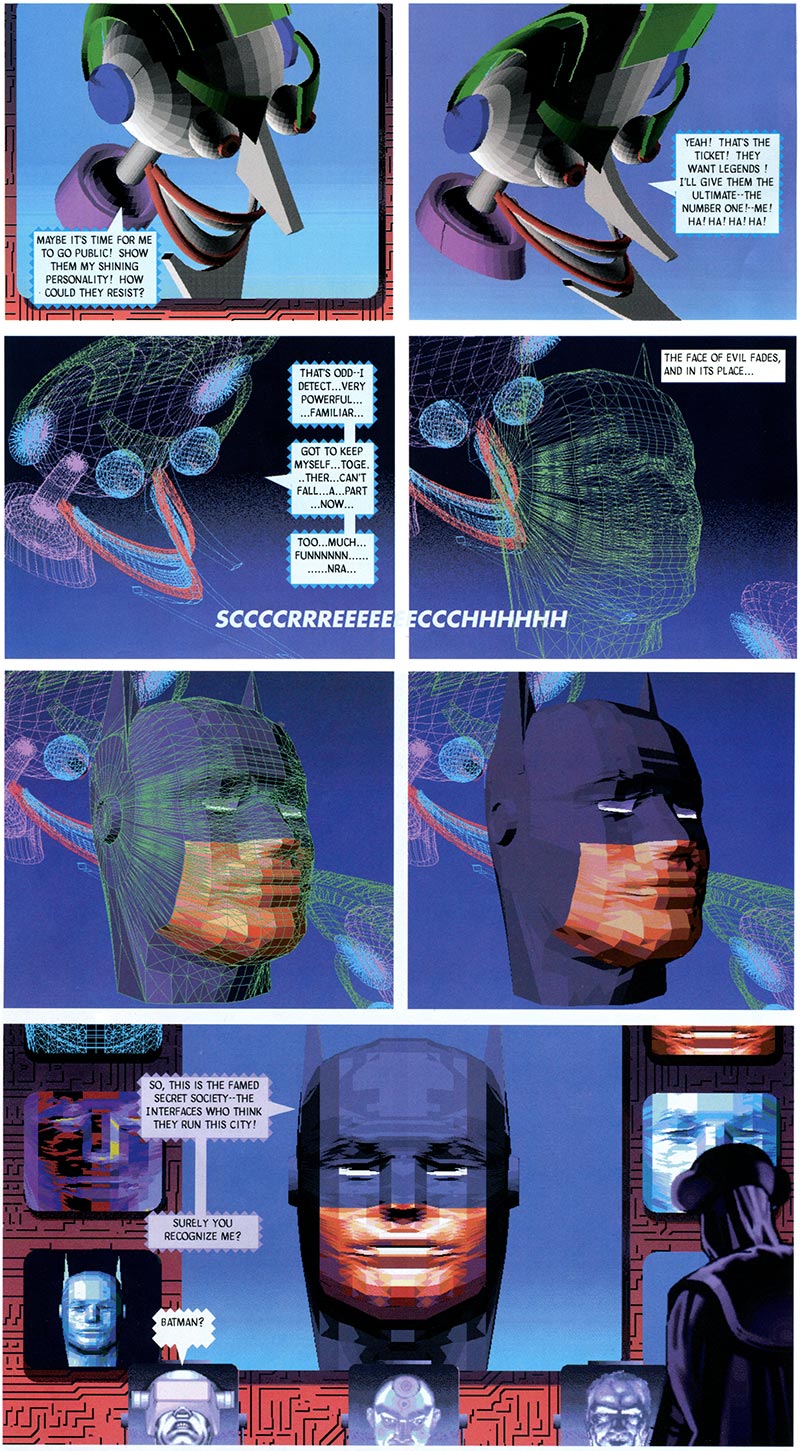

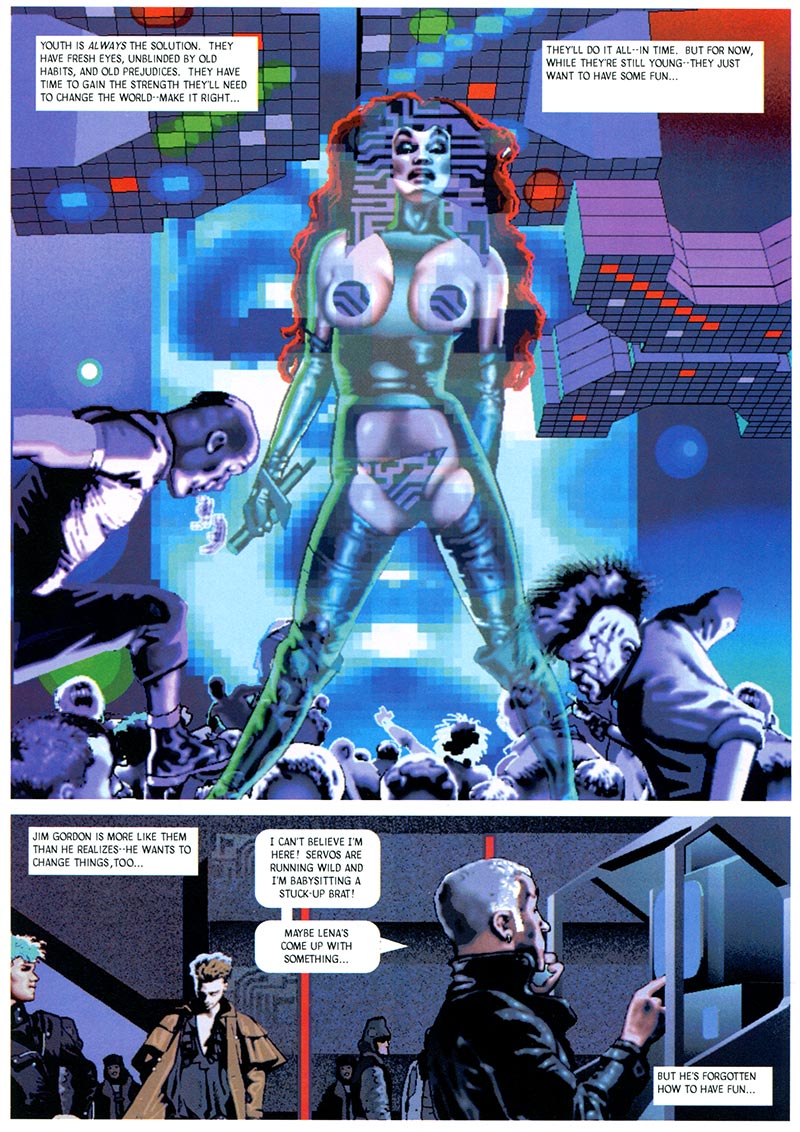

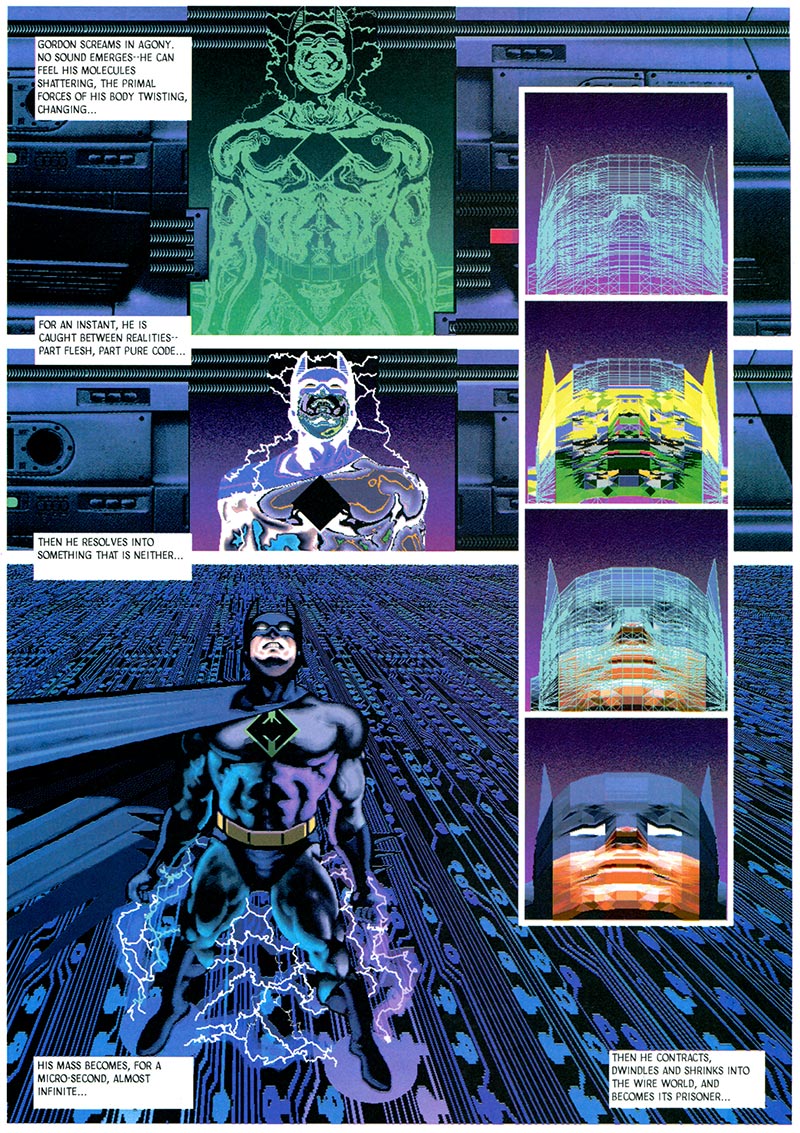

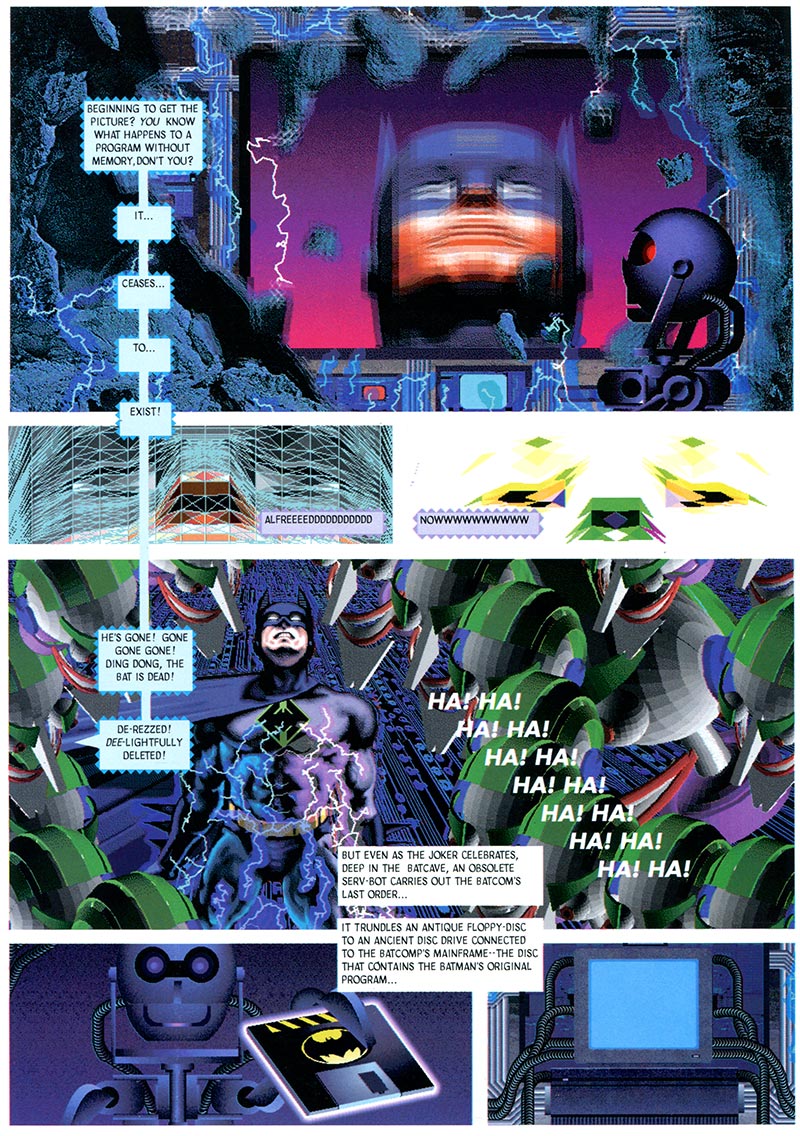

faster chips, more memory, bigger drives and falling prices brought with them higher resolution and a vastly expanded color palette: pixelization, "jaggies" and color-banding were beginning to give way to a richer and smoother result approaching traditional oil or airbrush and less harshly cg.like its predecessors, "digital justice" explores the consequences of all this brave new technology as gotham city, having once again succumbed to corruption "sometime in the next century", erupts in a cyber-showdown between two rival a.i. systems covertly left behind by their now-dead creators: a malignant "joker" virus and a no-longer silent "batcom" surveillance program.

a couple of old friends, peter gillis and mike saenz, showed me some rough printouts of a story that was produced entirely on a 128k apple macintosh computer, using but one disk drive. the artwork was chunky and brittle: it looked like some amphetamine addict had been given a box of zip-a-tone that suffered from a glandular disease. but the look was totally unique to comics. within several months, we refined the look and the resulting effort — shatter — was one of the best-selling comics of the year. it completely astonished the folks over at apple computer, inc., who never perceived such a use for their hardware.

we've come a long way in the past five years: the book you are now holding was produced on a macintosh computer that has 64 times the internal memory, 400 times the storage capacity, about 8 times the speed, and hundreds of software packages. more important, digital justice takes advantage of different devices that, five years ago, were barely dreamed of for the home or studio: computer-aided design, 3-d imaging programs, high-resolution and direct-to-film printers, graphics scanners, and color. a whole lot of color. in fact, there's the potential for more than 16 million colors. back then, naysayers and technophobes looked at the end result and, seeing only its shortcomings, declared the computer useless in the creation of comic art. since that time, that bottomless box has become so useful it is now almost invisible: artists have been using their machines to generate special effects, designers have been doing their design work online, letterers have been creating their own fonts, and craftspeople have been coloring comics with a palette (and the resultant special effects) heretofore unknown in the medium. dc comics even has its own in-house computer coloring department.

pepe wanted to turn cold computer technology into a warm "product" and to make the computer invisible. this is a formidable goal; there is a certain point an artist can reach wherein the end result no longer appears to be computer generated; at that point, the project will appear to be self-defeating. his early experiences with the commodore amiga computer and primitive art programs gave pepe a head start on the color macintosh ii. in creating the movie-like look of digital justice, pepe conceived and executed his work directly on the monitor with the electronic medium in mind. he used a wide variety of tools to bring the book to life: cad programs, vector illustration, 3-d modeling, text effects, and such paint programs as image studio, studio/8 and photoshop.

pepe then arranges these images into panels, and then, using quark xpress, the panels are assembled into pages, and finally, balloons, text and sound effects are added: the completed work ultimately is sent out so that printing negatives can be made directly from over 200 megabytes of computer files. no "physical artwork" is produced. indeed, the full color digital separations in digital justice represent a genuine technological breakthrough.

(story and art by pepe moreno)

Thursday, April 07, 2011

computer comix v3.0

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment